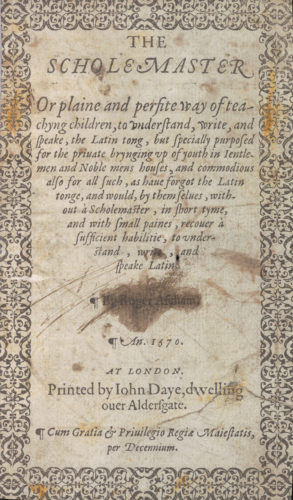

Once they could read and write in English, early modern schoolboys were also required to learn Latin. In theory, for older boys the schoolroom became an exclusively Latin space: they were supposed to speak in Latin at all times, even to each other. Roger Ascham’s The Schoolmaster (left) lays out a programme for teaching Latin grammar, but is itself written in English. Ascham was tutor to Elizabeth I, and was interested in the holistic education of students. Though the day-to-day grind of learning Latin grammar by rote may have seemed tedious to some, it unlocked the treasures of classical literature for generations of students. The print on the right, illustrating a scene from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, gives some idea of how vividly these texts could capture the early modern imagination, leaving their mark on literary and artistic works throughout the Renaissance. Here Daphne is caught mid-transformation, as she begins to metamorphose into a tree to escape Apollo’s amorous advances. In The Taming of the Shrew, Shakespeare imagines a painting of this scenario:

Daphne roaming through a thorny wood,

Scratching her legs that one shall swear she bleeds,

And at that sight shall sad Apollo weep,

So workmanly the blood and tears are drawn.

(Induction 2, 56-9)

In spite of its hardships, the schoolroom was a space that inculcated a knowledge of the classics which shaped the literary imagination of the Renaissance.