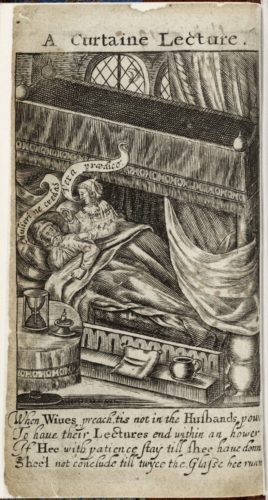

Not all marital encounters in bed were sexual. Curtain lectures – imaginative reconstructions of a wife’s lesson to a husband in bed – were a known genre in the period, famously represented in Heywood’s A Curtaine Lecture, and depicted on its title-page. Samuel Pepys reports in his diary his wife’s endless lectures to him in bed, in the wake of his affair with her maid (‘And so to bed – where my wife mighty unquiet all night, so as my bed is become burdensome to me’). Unwelcome as such knowledge might be, the force of women’s persuasive speech could be unleashed and sanctioned by the intimacy of the bedroom. The only space in the house where husband and wife were alone, the bedroom allowed for the reversal of social hierarchy and roles within a marriage, as well as for a transformation of the marital-bed into a school, a pulpit and a battle-ground. But Erasmus’ colloquy, ‘A Mery Dialogue’ (1523 in Latin, translated into English 1557), an early example of a wife’s speech to her husband in bed, has the wife present the marriage-bed as a place made for ‘pastyme and pleasure’, and warn against giving a husband ‘foule words in the chamber, or in bed’.

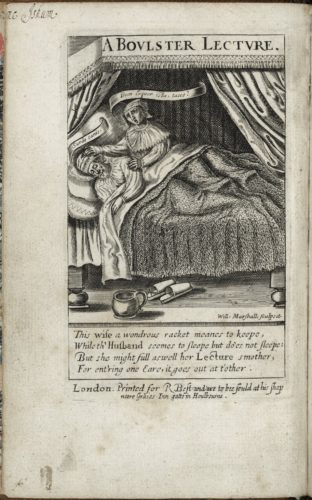

Note how curtains frame these scenes symbolically. Items associated with the space are used pictorially as well as verbally to define a space: curtains, pillows and slippers are used as emblems of intimacy and objects evocative of the bedroom. The image on the right, from Braithwaite’s ‘A Boulster Lecture’, reflects the satirical tone of the text by underlining the futility of the wife’s homily in the inscriptions: ‘And can you be silent even while I speak these things?’ (Wife) and ‘The dog was deaf’ (the husband pretending to be asleep). In both images, the bedroom is a culturally significant site that offers private knowledge of gender dynamics in the household, and social attitudes that nonetheless place and mediate these.