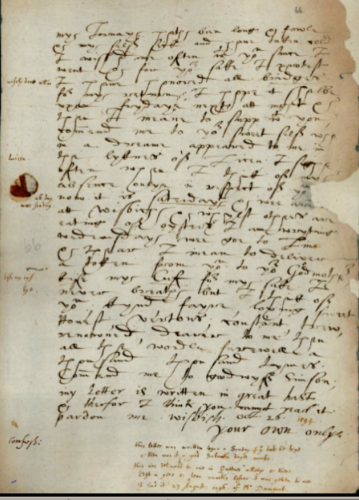

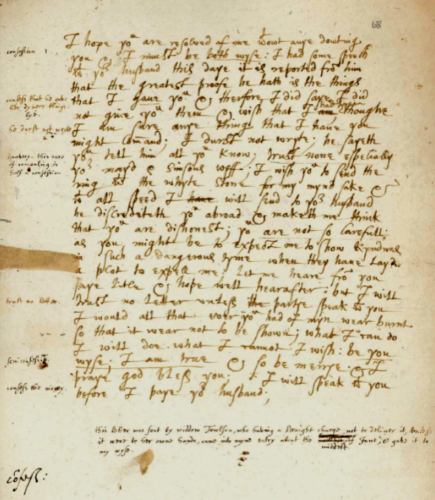

Here you can see two ‘exhibits’ – concrete objects which were meant to be demonstrative evidence – presented to the Cambridge University Vice Chancellor’s court in an adultery case in 1596. These are love-letters written by William Covell, Fellow in Divinity, Queens’ College, to Bridget Edmunds, wife of John Edmunds, employee of Peterhouse. Bridget, accused of adultery with Covell at the Ely diocesan court, requested a transfer of the case to the extraordinary jurisdiction of the V.C. Court, which had the power to try university members and other ‘privileged persons’ from the city. At this court, the letters were ‘openlie redd’, leading to an admission by Covell that they were written ‘with his own hand’.

The marginal comments, however, are in a different hand – John Edmunds’s. John had intercepted or procured these letters and annotated them over a period of two years, for presentation as evidence. John underlined details that would count as proof and help him prove the case; his comments are alternately legalistic and spontaneously condemnatory or sarcastic. As exhibits, these letters are supposed to offer unmediated legal knowledge. Yet what they bring alive is the mediation at the heart of proof - the process of the conversion of private acts into objects of public, institutional display, of intimate utterances into legal artefacts. Texts which become things, they suggest the ironic relation between persistent textual knowledge and the objective knowledge to which it is supposed to be reduced by the evidentiary context of the law-court.