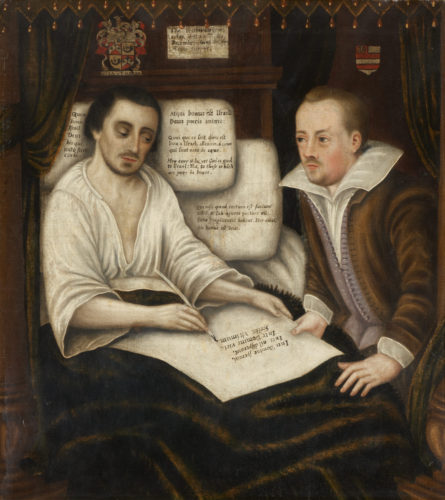

Any space – here, the intimate space of the bedchamber – can be turned into a legal space by the action performed and the structure of relations depicted. Making one’s last will and testament was at once a legal act and a deeply personal one. Braithwaite, with sunken eyes and clearly at death’s door, is propped up in bed writing his testament; another man sits very close, one hand holding the paper and the other resting on the dying man’s knees. This second man is Braithwaite’s friend and neighbour George Preston, to whom he left a legacy of £10.

The painting also sheds light on the social practice of portraiture: Braithwaite is identified, but not portrayed in a physically flattering way. Rather, it is his credit as a responsible householder that is foregrounded, as he is shown getting his earthly affairs in order before moving on to another life. This was a testamentary culture: the civil lawyer Henry Swinburne’s A Brief Treatise of Testaments and Last Wills (1590-91), written for a general readership, had quickly become the standard text on family law, and made this so-far obscure area of law suddenly accessible and much-discussed. The intimacy of Preston’s posture suggests the close relationship between the two men, to which the will becomes a lasting testament; but it also conveys the intimacy of the act of witnessing in these circumstances. At the same time, the painting itself becomes a visual proof of the validity of the will, turning the viewer, too, into a witness, and drawing them into the structures of interpersonal relations which create the legal space.

Click here to see another early modern deathbed in the Bedroom section.